[vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text]

How to achieve perfect focus and creamy backgrounds with every lens, every time!

Moving from auto settings to manual settings on your DSLR is one of the most intimidating steps a photographer takes. If you are feeling overwhelmed at all the things you have to learn in order to get your camera out of the auto section of the dial, rest assured that you are not alone.

If you are already well versed in your camera’s manual settings, this guide is still for you. Just scroll down a bit and skip the explanations of the exposure triangle and how the camera aperture works, and you will learn how to use depth of field, or DoF, to get the picture you want, every time.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”container-gusta” id=”container-gusta-menu-item-15849″ overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text]

The Exposure Triangle

The auto modes on your camera only control three things, believe it or not. When you choose the auto portrait setting, landscape setting, close-up setting, or sports setting, the camera’s computer sets these three controls in different ways to get the effect you want. In manual settings, instead of letting the camera make the decisions for you, you decide how you want those three settings to be. This gives you greater control of the exposure and lets you make the picture want, not the picture that your camera computer gives you.

These three controls are shutter speed, aperture, and ISO. Each one of them changes how much light hits the sensor. These are the three legs of the exposure triangle. The shutter speed is how long the shutter is open. The longer it is open, the more light hits the sensor, but the more risk you get for motion blur. The ISO is how sensitive the sensor is. If it is set very high, it is very sensitive to light and will make an image with even a small amount of light hitting it. But a very high ISO can also cause noise and graininess on the image. The aperture is how wide the shutter opens. When it opens very wide, it lets in a lot of light.

Each one of these controls lets you increase or decrease the amount of light that hits the sensor. If you increase the amount of light in one of the controls, you have to decrease it in another control. Similarly, if you decrease the amount of light in one of the controls, you have to increase it in another control.

The auto settings do all this work for you. In the sports setting, it sets the shutter speed to be very fast and the aperture at a medium size, and increases the ISO to compensate. In the closeup setting, it sets the aperture wide open and the shutter speed fast, and then adjusts the ISO to achieve the right exposure for the lighting. In landscape mode, it closes the aperture as much as possible, slows down the shutter speed a bit, and increases the ISO. As you can see, each of these controls changes how much light reaches the sensor, but each also creates a different effect in the picture. The biggest rule to remember is that if you increase the light hitting the sensor in one part of the exposure triangle, you have to decrease it in another part.

In this guide, we are going to be talking about the aperture, as it is the part that controls the depth of field.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”container-gusta” id=”container-gusta-menu-item-15853″ overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text]

What is the aperture?

Hold your DSLR with the lens facing you and take a picture of yourself. Be sure to look straight into the lens while you do this, so you can see what happens. You should see the shutter blades open and create a hole, and then close back together. The distance they open is called the aperture.

In manual and aperture-priority modes, you control how far the shutter opens when you take a picture. The aperture setting is also referred to as an f-stop. The largeness and smallness of the aperture depends on the lens you are using. With most kit lenses (the ones that automatically come with your camera body), you will usually have an aperture range of about f/4 to f/22 or so. You can get lenses with different aperture ranges – one of the most popular lenses on the market, across all manufacturers, is the 50mm f/1.8 or 1.4.

The numbers for apertures are backwards, as they are for gauge measurements. Small numbers represent large openings, and large numbers represent small openings. So an f-stop of 1.4 is a huge opening, and an f-stop of 22 is a tiny opening. The size of the aperture affects the amount of light hitting the sensor, and it also dramatically changes the look of your picture.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”container-gusta” id=”container-gusta-menu-item-15854″ overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text el_id=”link3″]

What is Depth of Field?

The size of your aperture changes your depth of field. So what is depth of field?

Put simply, depth of field is how much of your picture is in focus.

When you take a picture, you have a space of distance in front of you. That entire space may be in focus, or only a part of it may be in focus, depending on your aperture settings. For example, in a landscape picture, you may have everything from the plants in the foreground to the distant mountains in focus and perfectly clear. In a closeup of a flower, you may have the flower sharp and in focus and the background blurry. In a portrait, you may have the foreground blurry, the person sharp, and the background blurry again.

Many people think that blurry backgrounds are achieved by, say, going over everything except the subject (the person, or flower, or whatever you are trying to take a picture of) with a tool in a computer program to make it blurry. Some people do that, but this is not at all what we are talking about. We are talking about using your camera settings to achieve these creamy backgrounds and sharp focus in the camera.

When you are deliberately blurring the background in-camera, it is not just the person or object that you are photographing that is clear. Everything that is that same distance away from the camera as the subject you are photographing will be clear. Your depth of field is the distance of clearness that you have. If you have a very small distance that is clear and in focus, and most of the space in front of you is out of focus (as when you have a close-up of a flower or a portrait with a very creamy and blurred background), you have a narrow or small depth of field. When you have a large distance that is clear and in focus (as when you have a landscape where objects in the foreground and in the background are both clear), you have a wide or large depth of field.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”container-gusta” id=”container-gusta-menu-item-15856″ overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text]

How Does DOF Work?

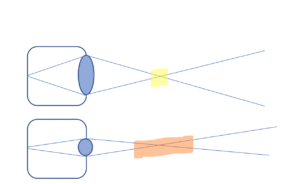

The size of your depth of field is a product of the direction of the light that comes into the lens and hits your camera sensor. Diagram 1 shows the physics of focusing with a large aperture, and Diagram 2 shows it with a small aperture.

Diagram 1

The point where the lines intersect represents the focal point. This is the exact point where the image is going to be perfectly in focus. However, there is also a space in front of and behind the exact focal point where the objects will be clear. In the diagram, this area is represented where the intersecting lines are close together. When the two intersecting lines become too far apart from each other, light reflecting off of objects in those areas will diverge on the sensor, instead of coming to a point. In other words, those objects will be blurry.

The area where the two intersecting lines are close enough together to make a clear image is called the depth of field, which is often shortened to DoF. It is common to talk about objects within the depth of field being “in focus.” To be completely accurate, we should note that only the objects that are exactly the same distance away as the specific focal point are truly in focus. If you were to blow your picture up to the size of a wall, if your camera body had enough image resolution to handle such a big image, you would start to see blurring everywhere that is not precisely on that focal plane. But, presumably, you are not taking images that you are going to enlarge to the size of a building.

Therefore, in the photography industry, “in focus” is considered to be where the details would look clear at a certain print size and viewing distance. Most often, this is defined as the image being printed as an 8×10 and the viewer standing a foot away. So even though only the specific focal point is technically in focus, the depth of field is the area in front of and behind the focal point where details will appear to be in focus to someone standing a foot away from an 8×10 print of the image.

As you can see, when the aperture is large, the DoF narrows. The angles of the light that hits the sensor, as represented by the intersecting lines in the diagram, only have a small amount of space in which they are close enough to make a clear image. Everything in front of and behind the depth of field is going to be blurry.

On the other hand, when the aperture is small, the depth of field is wider. The angles are much smaller, and the area in which the intersecting lines are close to each other is much larger. This means that wherever your focal point is in your pictures, objects in front of and behind it will be in focus.

This means that the distance that objects will be in focus in front of and behind the focal point depends on the exact size of the aperture. The larger the aperture (the smaller the number), the smaller the amount of space that will be in focus. The smaller the aperture (the larger the number), the greater the distance that will be in focus.

Circle of Confusion

The area in which objects seem to be “acceptably clear” is known as the circle of confusion. If you use an online depth of field calculator, it will probably set the circle of confusion to the above listed parameters: 8×10” print, 1-foot viewing distance. However, if you plan on enlarging the picture to the size of the wall, you will want to change your accepted circle of confusion in your DoF calculator. Remember: this is a value you decide. It is how much wiggle room you have in defining what is “acceptably clear.” If the picture is going to be printed small, you have a lot of wiggle room. Your circle of confusion increases. If the picture is going to be printed huge, the blurry areas are going to become apparent much more quickly. Your circle of confusion decreases.

To clarify: the depth of field is the area within the circle of confusion. It is the space in which all objects will look clear enough. Only the focal plane itself is perfectly in focus. But when you print out your picture and hang it up, objects in front of and behind the focal plane will look acceptably clear. If you zoomed in on your computer or printed out an absolutely massive copy of your picture, some of the areas that used to be acceptably clear would start to look blurry. Therefore the depth of field is an area in which viewers are confused, or tricked into thinking that the objects are clear; they’re not really, but at a particular size print and a particular viewing distance they look clear.

For the purposes of this guide we will assume that the circle of confusion is going to remain standard. We’re going to assume that you’re taking pictures which people may want enlargements of, and probably won’t be sticking to wallet sizes, and also that you won’t be putting them on the side of a building. If you do plan on putting your photo on the side of a building, just remember to note that in your DoF calculator.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”container-gusta” id=”container-gusta-menu-item-15858″ overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text]

Calculating Depth of Field

Up to now, our explanation of the size of the depth of field has been fairly vague. If the aperture is wide open, the depth of field is very small. If the aperture is closed and small, the depth of field is very large. For a set of people who rejoice in numbers and precision when it comes to their equipment, terms like “larger” and “smaller” are somewhat meaningless. There may be readers who are saying, right now, “What does that even mean, that the depth of field is ‘big’? How in the world do I know how big it is?”

You can, of course, calculate your DoF down to the closest 1/16th of an inch. Most people don’t. These calculations depend on the lens length or zoom distance, the distance away the subject is from the camera, and of course the size of the aperture. Even the particular camera body you use affects the size of your depth of field. Since most people do not bring a tape measure with them to a photo sheet and do complex math equations before taking a picture, this is not something that photographers in general worry about getting perfectly precise.

There are many depth of field calculators you can find online, and even quite a few phone apps so you can reference them when you are out doing a shoot. Again, unless you are bringing a tape measure with you to every photo shoot, these will not enable you to be absolutely precise with your measurements. But if you are able to estimate whether your subject is two feet away from you, ten feet away from you, or twenty feet away from you, you will be able to ballpark your measurements well enough for your depth of field calculator to tell you what aperture to use to get the effect you want.

Even if you are just estimating distances instead of measuring them precisely, a DoF calculator can still help you make sure you get everything in focus that you want. There is nothing worse than taking a picture and realizing that the focus was just barely off, or that your entire subject or group of people weren’t in focus!

Relative Depth of Field

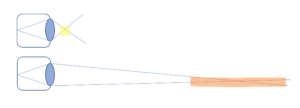

As we touched on above, depth of field depends on your aperture setting as well as your distance from the object you are focused on. The farther you are from your focal object, the greater your depth of field becomes — even if you don’t change the aperture.

In the diagram above, the aperture remains the same. The only thing that changes is the focal distance. When the focal point is close to the camera, the depth of field is very narrow. When the focal point is far away from the camera, on the other hand, the depth of field is quite wide.

Using the Depth of Field Preview Button

Most DSLR and SLR cameras have a depth of field preview button. This is usually a small button right next to your lens. If you are not sure where your depth of field preview button is, check the owner’s manual of your camera. The exact location and appearance of the depth of field preview button varies from camera body to camera body, but it will usually be somewhere near the lens.

As the name of the button suggests, the DoF preview button lets you preview what the depth of field will be on the picture. When you look through the viewfinder, you see everything clearly. What you are actually seeing is the image that is coming through the lens, reflected into the viewfinder by a mirror. You aren’t seeing the effects of your aperture or shutter settings. The DoF preview button lets you see the effects of your current aperture settings before you take the picture.

The depth of field preview button is extremely useful for making sure your settings are the way you want them to be, especially if you only have the chance to take one picture and want to make sure you get it right.

There are some things to remember about the DoF preview button. On some camera bodies, it darkens the areas that will be out of focus instead of blurring them. This is just as useful for predicting what the effect of the aperture setting will be as blurring it is, but it can make it harder to see what you are looking at. Keep in mind that the DoF preview button is not showing you the light settings of your camera – in other words, it is not showing how overexposed or underexposed the picture will be. It is simply showing you where the picture will be sharp, and where it will not.

The DoF preview button is great for letting you see if distracting background elements will be blurred out at your current settings. If you are photographing a group of people, it is invaluable for ensuring that everyone is in focus and that no one will be blurry.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”container-gusta” id=”container-gusta-menu-item-15860″ overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text]

Bokeh

So if you have to try so hard to make sure everyone is in focus … why not just set your aperture always at the smallest setting possible (largest number) so you can be sure that everything will be in focus?

Because of bokeh, that’s why.

Bokeh is that smooth, creamy blurriness in the background. It happens when objects are so far outside your depth of field that all detail disappears and they basically become fuzzy blobs of color.

The quality of your bokeh depends on your quality of glass. Your kit lens is usually capable of achieving some blurry backgrounds, but it is not likely to give that really rich, creamy bokeh that you’ll find in really high end photography. In this area, glass quality really matters. A cheap lens will not give anywhere near the beauty of bokeh that you will get with higher quality lens.

So if you don’t have a couple thousand dollars to drop on a lens, are you doomed to not having bokeh in your pictures? Not at all! You can easily achieve bokeh effects even with a kit lens, albeit with some more irregularities in the bokeh than you would get with a better lens. You may see some boxiness in your bokeh shapes, faint lines, or even double outlines. These are all tiny waves and irregularities in your lens showing up in your pictures. But everyone will be too busy looking at the subject you took the photo of to notice these small irregularities in your bokeh. After all, the whole point of bokeh is to draw attention to the main subject matter and make everything else literally fade from view.

Bokeh artistry

When we look at anything, our brains automatically filter out all non-essential information. When we take a picture, on the other hand, all the information is right there. Nothing is filtered out. So while you might not even notice the awkward people standing way off in the distance when you’re at an outdoor wedding watching the bride and groom get hitched, take a picture of the same scene and suddenly those background people will get very distracting.

Your eyes don’t actually blur the things you aren’t focusing on. But bokeh helps to create a similar effect in a static photo as focusing on something with your eyes by blurring out distracting details. The most basic purpose of bokeh is to approximate through art the psychological experience of being there at the scene.

Bokeh can make a boring or ugly scene look amazing. It hides the details of the background, so all you see is the light and color. It makes your portraits look professional, and makes even everyday scenes look magical.

To maximize your bokeh, you will want an open shutter speed and careful placement. You need to be close to your subject, and you also need your subject to be as far as possible from the background. Be careful: if you start moving too far away from your subject, your bokeh will become less blurry, even if your aperture is wide open. If you want a lot of bokeh, shorten your depth of field by getting up close and personal with your subject.

You can even create custom bokeh shapes! Take a black piece of paper, cut a circle the size of your lens, and cut out a shape in the middle. Take a picture with a wide-open aperture, making sure there are lights in the background, and you will see that the bokeh spots are in the shape you created. This works especially well with Christmas lights, street lamps, and candles.

The sweet spot, shooting wide open, and how to get maximum sharpness

You might expect from the above explanations of how depth of field works, that the focal plane of an image will always be perfectly sharp and areas behind and in front of it will be varying degrees of blurriness depending on your settings. But this is only half true. Yes, the background and foreground will be varying degrees of blurriness depending on your settings. No, your focal plane will not always be perfectly sharp at every aperture.

Every lens has a “sweet spot,” which is the aperture at which it focuses most perfectly. To find your lens’s sweet spot, you will just need to experiment until you find it. You will have to take the same picture over and over again, from your smallest aperture setting to your largest one. (You will also need to change your ISO and/or shutter speed to compensate for the change in exposure, of course.) Then, look at all the pictures on your computer. Whichever picture has the clearest image of the object you focused on, that is the aperture setting that is your lens’s sweet spot. You can view the exif data, which shows all the settings for each photo, on most photo viewing and editing programs. Many lenses have a sweet spot somewhere around f/7. But even if you don’t know your lens’s sweet spot, there are different things you can do to make sure your images have a nice sharp focus.

When you shoot wide open, you will often get a certain amount of softness in your image. Even if your subject is perfectly in focus, you may lose some details and sharpness. This is especially noticeable in lenses that have very large apertures, such as f/1.4 or f/1.8.

There is an easy solution to this, though: just shoot with your aperture stopped two stops up from maximum instead of all the way wide open. You will still have a narrow depth of field and a huge amount of bokeh, but your subject will be nice and sharp.

Shooting wide open on a lens with a large aperture can also cause some distortion in your picture. Some lenses will show vignetting, or darkening around the edges, with a wide open aperture. The vignette can be removed in post-processing, or it can be left in as an artistic effect. As with everything your camera does, these effects can be tools for creating powerful images. If they aren’t the look you are intending to get, though, they can spoil your picture. Being aware of the effects of shooting with a large-aperture lens “wide open” can help you get the picture you want and ensure that it is just as sharp and clear as you want it to be.

So if shooting with a large-aperture lens wide open makes your pictures turn out soft and less sharp, why do people spend big bucks on large-aperture lenses? Several reasons. Firstly, there are times when you want to shoot wide open even if the focus will be softer. If you are in a low light situation and you can’t use flash, opening your aperture up all the way can let you take pictures without making your shutter speed impossibly slow and risking getting motion blur. Having one or two extra f-stops available can exponentially increase the amount of light that gets let in, and save what might have been an impossible lighting situation. Secondly, even if you never open your aperture up all the way, having a lens that can open to f/1.4 or f/1.2 allows you to set it to 1.8 or 2.0, get a nice thin depth of field, and have a much sharper picture than you would have gotten by setting an f/1.8 lens to the same aperture. And, naturally, if you have a kit lens with a maximum aperture of f/4, investing in a lens with a maximum aperture of even f/1.8 will be a game-changer in terms of the light settings you can work with and the artistic effects you can get. Therefore, whether you shoot “wide open” or not, a high quality lens with a large aperture can vastly increase the quality of pictures you get, especially when it comes to portraits and close-up photography.

When you are shooting with a narrow depth of field, these recommendations can help you increase the sharpness you achieve. Set your aperture slightly smaller than the maximum setting to reduce the softness and distortion of shooting wide open. Increase your shutter speed to reduce blur. If you are in a low-light situation, consider using an off camera flash to freeze motion and allow you to reduce your ISO. Focus very carefully – when your depth of field is narrow, it becomes very apparent very quickly when your focus is wrong. A super wide aperture on a close up portrait can result in part of the face being in focus and part being blurry. You do not want the part that is in focus to be the eye that is farthest away from the camera![/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”container-gusta” id=”container-gusta-menu-item-15861″ overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text]

Distance from backgrounds and backdrops

Your depth of field is perhaps the most important factor in where you place your subjects relative to the background. Before you pose anyone, decide the overall effect you want. Do you want your subjects to be clear and isolated against a blurry background? Or do you want them to be solidly placed in the situation, with a clear background so that everyone can see what a beautiful location they are in? This will determine both where you have them pose and what aperture settings you want to choose.

Every picture you take tells a story. What is the story you are telling with this particular photo shoot or this individual image?

When do you want your subjects isolated from the scene? Some easy answers: when the scene is not particularly pretty, when the scene is not important, when the story about the people is much more important than the story about the scene, when the scene is distracting, and when the scene exists to support the subjects rather than the subjects existing within the scene. This last point might be confusing, but think about it this way: when you are taking photos of a wedding, you might do a close-up of the bride and groom kissing with the altar and flowers blurred in the background. The point of the scene was their marriage, not necessarily the church or venue where they were married. If you are doing family photos in the local park, you and your clients probably chose that venue because it was convenient and vaguely pretty. You will probably want to get quite a few shots with the people isolated from the background. If you are doing candid shots at an event where there is a lot going on and the background is very busy and distracting, you will definitely want to get in close for individual shots, with a narrow depth of field and a blurred background.

When do you want your subjects to be part of the scene around them? Basically, when the scene is pretty enough to warrant it, or when it is important to the story. If you have a couple who is having a destination wedding in Rome, they are going to want the church or basilica where they got married to be clear and prominent in at least some of their wedding pictures. If you’re doing an urban engagement shoot or set of senior photos where you’re highlighting the architecture and the bustling energy of the city, you’ll want the background to be sharp. If you’re doing a portrait on an impressive landscape, you want the landscape to also be in focus.

Basically, if the story you are telling focuses primarily on the person or people you are photographing, isolate them from the background. If the story you are telling focuses on your subjects being in the scene, bring the scene into the photo.

How do you isolate your subjects from the background? Place them farther from the background, bring yourself closer to the subject, and increase your aperture (keeping in mind whether you have a group of people who all need to be in focus, or any other considerations there may be about your depth of field).

How do you integrate your subjects in the scene you are photographing? Decrease your aperture (remember, this means setting it to a higher number), move farther away from your subjects, and/or zoom out so they fill less of the frame. You can place your subjects closer to the background, but you can also have them closer to the camera if you want them to be more prominent. The placement of your subject in this situation is entirely up to the artistic and narrative effect you want to create. While it is imperative that the subject be removed from the background if you want a smooth, blurry background, it does not matter so much where the subject stands if your aperture is small and you want the background to be clear.

You may also work with backdrops, either in a studio setting with a fabric backdrop or outside with an interesting wall. If your subject is standing right in front of the backdrop, as is conventionally done, the backdrop will not be blurry no matter what your aperture setting is. The depth of field you need in this situation will be about 2-3 feet, depending on exactly where you set your subject. Therefore you have a lot of flexibility in your settings – you do not need either a very large or a very small depth of field, and therefore you can set your aperture to be basically anywhere as long as the depth of field is large enough to catch both the subject and the backdrop. Many photographers use f-8 or so when they are working with backdrops, though this naturally depends also on the lighting situation.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”container-gusta” id=”container-gusta-menu-item-15862″ overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text]

The “I don’t care” zone

The mid range of f-stops, f/7 to f/11 or so, is often affectionately referred to as the “I don’t care” zone. It’s also overwhelmingly ignored by photographers. It’s easy to see why – these settings don’t give you nice creamy bokeh, and they also don’t give you crisp sharpness all the way through the photo. So why would you want to use this range of aperture settings, where the depth of field is fairly wide but doesn’t extend all the way through the picture?

As was discussed above, many lenses have a “sweet spot” somewhere in the mid range of aperture settings. This is a good reason to use this range of settings, especially if you are taking a picture where it does not really matter if the background is clear or blurry. When there’s not a compelling artistic reason to use another setting, why not use the one that will give you the most sharpness?

Even if you haven’t yet taken the time to find your lens’s sweet spot, it is true of most lenses that pictures taken in the f/7-f/11 range tend to be clearer and have less distortion than pictures taken at either extreme. For this reason, mid-range apertures are a good way to play it safe. If the lighting is bright enough that a mid-range aperture will not require either an extremely high ISO or a dangerously low shutter speed, you can maximize the chances that your pictures will turn out by using a mid-range aperture in the “I don’t care” zone.

The mid-range aperture gives you a depth of field that takes up a good portion of your photo, though not quite all of it. This means that even if your focus is slightly wrong, chances are the subject you were aiming to photograph will be clear. While obviously the goal is to get the focus right all the time, it doesn’t hurt to have a failsafe so that your clients will not be disappointed or you won’t miss the moment even if you mess up your focus.

Many professional photographers use mid-range apertures when they are taking pictures of groups and when they are shooting against backdrops. This is because the mid-range apertures give the most sharpness and the least distortion, and they virtually eliminate the chance that someone in the group will be out of focus.

Mid-range apertures can also be used very effectively for landscapes. Remember that your depth of field depends not only on your aperture, but also how far away you are from the subject you are focusing on. If you choose an f/8 or an f/11 aperture and then focus on something fifty feet away from you, you are going to have a very large depth of field. If you have a shot where you want to get both the flowers at your feet and the mountains in the distance in focus, you may well want the f/22 setting. On the other hand, if you have a landscape that is not so expansive, an f/7-f/11 aperture might easily be able to give you the depth of field you need. The benefit of shrinking your depth of field to as small as you need it to be, rather than choosing an aperture that gives you a much bigger depth of field than you need, is that it allows you to choose a faster shutter speed. In landscape photography, even with a bright sun, this might mean the difference between being able to hold your camera in your hand and needing to use a tripod.

The mid range is a fantastic choice for street photography. Usually in street photography, you want to capture an entire scene, rather than separating out one person or object and leaving the rest blurry. This is not to say that a narrow depth of field is wrong for street photography – in fact, Brandon Stanton, the photographer behind Humans of New York, uses a narrow depth of field to isolate the people he photographs and emphasize their uniqueness as individuals – but simply to point out that if your goal is to take a picture of a scene, a mid-range aperture can serve you very well. It can ensure that you get details in a wide area, thus giving richness and depth to your storytelling, while also letting in enough light to keep you from having to slow your shutter speed down too much.

Bear in mind, with these recommendations for using the mid range of aperture settings, that depth of field is relative. It becomes shorter when focusing on objects close to the camera, and longer when focusing on objects far away from the camera. So if you set your aperture to f/8 and then take a close-up shot of a flower, the background is probably going to be fairly blurry. But if you take a picture of a car 20 feet away, you will get sharpness for quite a way in front of and behind your subject.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”container-gusta” id=”container-gusta-menu-item-15863″ overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text]

Hyperfocal distance

And now we come to one of the most complicated and counterintuitive aspects of depth of field: the hyperfocal distance.

The depth of field increases as you focus farther away from the camera. This much is clear. You might expect this process to increase gradually and indefinitely, where focusing 1 foot away might give you a depth of field of 2.5 feet, focusing 3 feet away might give you a depth of field of 5 feet, and focusing 10 feet away might give you a depth of field of 20 feet or so. (These numbers are all hypothetical, especially since we have not even established what aperture and focal length we are talking about.)

However, as it happens, the process of increasing the depth of field does not happen in a linear or gradual fashion at all. Up to a certain point, it does, and then it reaches a point at which the depth of field suddenly extends from half the hyperfocal distance to infinity – literally to as far in the background as there is anything to photograph. This is called the hyperfocal distance. If you focus at or slightly past the hyperfocal distance, if there are stars in the sky they will be in focus.

How to calculate the hyperfocal distance? As with all other aspects of depth of field, the hyperfocal distance for your camera setup depends on your camera body, the focal length you are shooting at, and the aperture you are using.

When you are strategizing about using depth of field in general, it can be perfectly sufficient to experiment and just get a general knowledge of what sort of depth of field you get at different settings with your camera, if you don’t want to use a DoF calculator. It is always better to know for sure, but you can get away without being absolutely precise. But if you are using the hyperfocal distance, you need to know.

Remember, if you focus at or slightly past the hyperfocal distance, you will have sharpness from halfway between the camera and the focal point, all the way to infinity. But, if you focus even an inch short of the hyperfocal distance, you will end up with a shorter depth of field and a background that is blurry. Therefore you need to be absolutely sure you know your hyperfocal distance, and also for good measure you will want to focus a little bit past the hyperfocal distance. By focusing a little bit beyond the hyperfocal distance, you may lose a small amount of sharpness in the foreground, but you ensure that your background is going to be sharp. When it comes to shooting breathtaking landscapes, you do not want to take any chances.

So how do you know what your hyperfocal distance is at any given setting? The best way to find out is simply to use a depth of field calculator. You will plug in your desired aperture setting and your focal distance (remember, focal distance is the length of your lens or how far you are zoomed in, not the distance to the subject you are focusing on), but not the focal distance. Select the closest focal distance that shows the upper limit of the depth of field to be infinity, which is indicated by a figure 8 on its side. This is the hyperfocal distance for your given settings.

To use the hyperfocal distance, compose the scene as you want it in your camera. Put your camera down, and go place an object about a foot farther away from the camera than the hyperfocal distance. The extra foot of distance is to give yourself some room for error. Or you could have a friend go stand in that spot. Focus your camera on the person or object that you have placed slightly beyond the hyperfocal distance. Then, switch to manual focus mode on your camera. Remove the object or have the person step away, and shoot the picture.

The reason for setting your camera on manual focus mode is that it lets you take the picture at the focal distance you set it for, without automatically refocusing when you press the shutter. If you have your camera set to back-button focus, you do not need to turn it to manual. Simply don’t press the focus button when you go to take the picture. But if your camera automatically focuses when you press the shutter down halfway, you will definitely need to move it to manual focus after you have set the focal distance.

Now that you know

Depth of field is an essential tool for every photographer to know how to use. When you know how to use depth of field, you can use it to enhance your storytelling and make your photos stand out. Knowing how to use depth of field takes your photos will let you take your photos from pretty to stunning. Now that you know what depth of field is and how to use it, you can start to experiment with it and discover how to make it work for your style. With every step from automatic to manual, you gain greater control over your photos and the effects you can achieve with them. When you control your depth of field and are able to use it as a tool in your photography, you become a better portrait photographer, a better storyteller, and a better landscape photographer. We hope you enjoy putting this tool to use and letting it transform your photography![/vc_column_text][vc_raw_js]JTNDc2NyaXB0JTIwdHlwZSUzRCUyMnRleHQlMkZqYXZhc2NyaXB0JTIyJTNFJTIwJTBBalF1ZXJ5JTI4ZG9jdW1lbnQlMjkucmVhZHklMjhmdW5jdGlvbiUyOCUyMCUyNCUyMCUyOSU3QiUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyNCUyOCUyMi5wdXJwb3NlLW5hdmlnYXRpb24lMjBsaSUzQWZpcnN0LWNoaWxkJTIyJTI5LmFkZENsYXNzJTI4JTIyY3VycmVudC1tZW51LWl0ZW0lMjIlMjklM0IlMEElMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjQlMjglMjIucHVycG9zZS1uYXZpZ2F0aW9uJTIwbGklMjIlMjkuYWRkQ2xhc3MlMjglMjJzbW9vdGgtc2Nyb2xsJTIyJTI5JTNCJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTI0JTI4JTIyJTIzbmF2LTEwODI3MTkzNzQ1YWFhNzE4NmI0NzM3JTIwc2VsZWN0JTIyJTI5LmFkZENsYXNzJTI4JTIyc21vb3RoLXNjcm9sbCUyMiUyOSUzQiUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyNCUyOCUyNy5jb250YWluZXItd3JhcCUyNyUyOS5jc3MlMjglMjd6LWluZGV4JTI3JTJDJTIwJTI3aW5oZXJpdCUyNyUyOSUzQiUwQSUyMCUyMCUwQSUyNCUyOCUyNy5ndXN0YS1zZWxlY3QtbmF2JTIwc2VsZWN0JTI3JTI5LmNoYW5nZSUyOGZ1bmN0aW9uJTI4JTI5JTIwJTdCJTBBJTIwJTIwdmFyJTIwaGFzaCUyMCUzRCUyMCUyNCUyOHRoaXMlMjkudmFsJTI4JTI5JTNCJTBBJTIwJTIwdmFyJTIwZGVzdCUzRDAlM0IlMjAlMEElMjAlMjBpZiUyMCUyOGhhc2glMjElM0QlMjclMjclMjklMjAlN0IlMEElMjAlMjAlMjAlMjBpZiUyOCUyNCUyOGhhc2glMjkub2Zmc2V0JTI4JTI5LnRvcCUyMCUzRSUyMCUyNCUyOGRvY3VtZW50JTI5LmhlaWdodCUyOCUyOS0lMjQlMjh3aW5kb3clMjkuaGVpZ2h0JTI4JTI5JTI5JTdCJTIwJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwZGVzdCUzRCUyNCUyOGRvY3VtZW50JTI5LmhlaWdodCUyOCUyOS0lMjQlMjh3aW5kb3clMjkuaGVpZ2h0JTI4JTI5JTNCJTIwJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTdEJTIwZWxzZSUyMCU3QiUyMCUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMGRlc3QlM0QlMjQlMjhoYXNoJTI5Lm9mZnNldCUyOCUyOS50b3AlM0IlMjBkZXN0JTIwJTNEJTIwZGVzdCUyMC0lMjA5MyUzQiUyMCUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCU3RCUyMCUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyNCUyOCUyN2h0bWwlMkNib2R5JTI3JTI5LmFuaW1hdGUlMjglN0JzY3JvbGxUb3AlM0FkZXN0JTdEJTJDJTIwMTAwMCUyQyUyN3N3aW5nJTI3JTI5JTNCJTIwJTBBJTIwJTIwJTdEJTBBJTdEJTI5JTNCJTIwJTBBJTBBJTIwJTIwJTBBJTIwJTIwJTI0JTI4d2luZG93JTI5LnNjcm9sbCUyOGZ1bmN0aW9uJTI4JTI5JTdCJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwaWYlMjAlMjglMjQlMjh3aW5kb3clMjkuc2Nyb2xsVG9wJTI4JTI5JTIwJTNFJTNEJTIwMjIwJTI5JTIwJTdCJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTI0JTI4JTI3JTIzc2VjdGlvbi13aWRnZXQtMTU4NjklMjclMjkuYWRkQ2xhc3MlMjglMjdkbm9uZSUyNyUyOSUzQiUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCU3RCUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMGVsc2UlMjAlN0IlMEElMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjQlMjglMjclMjNzZWN0aW9uLXdpZGdldC0xNTg2OSUyNyUyOS5yZW1vdmVDbGFzcyUyOCUyN2Rub25lJTI3JTI5JTNCJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTdEJTBBJTdEJTI5JTNCJTBBJTBBJTIwJTI0JTI4d2luZG93JTI5LnNjcm9sbCUyOGZ1bmN0aW9uJTI4JTI5JTIwJTdCJTIwJTIwJTIwJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwaWYlMjglMjQlMjh3aW5kb3clMjkuc2Nyb2xsVG9wJTI4JTI5JTIwJTJCJTIwJTI0JTI4d2luZG93JTI5LmhlaWdodCUyOCUyOSUyMCUzRSUyMCUyNCUyOGRvY3VtZW50JTI5LmhlaWdodCUyOCUyOSUyMC0lMjAzNzAlMjklMjAlN0IlMEElMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjQlMjglMjIucHVycG9zZS1uYXZpZ2F0aW9uJTIyJTI5LmFkZENsYXNzJTI4JTIyZG5vbmUlMjIlMjklM0IlMEElMjAlMjAlMjAlN0QlMEElMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjBlbHNlJTIwJTdCJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTI0JTI4JTIyLnB1cnBvc2UtbmF2aWdhdGlvbiUyMiUyOS5yZW1vdmVDbGFzcyUyOCUyMmRub25lJTIyJTI5JTNCJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTdEJTBBJTdEJTI5JTNCJTBBJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTI0JTI4d2luZG93JTI5LnNjcm9sbCUyOGZ1bmN0aW9uJTI4JTI5JTIwJTdCJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTI0JTI4JTIwJTIyLnZjX3Jvdy5jb250YWluZXItZ3VzdGElMjIlMjAlMjkuZWFjaCUyOGZ1bmN0aW9uJTI4JTIwaW5kZXglMjAlMjklMjAlN0IlMEElMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjB2YXIlMjB2YWx1ZSUyMCUzRCUyMDAlM0IlMEElMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjB2YXIlMjByb3dfaWQlMjAlM0QlMjAlMjQlMjh0aGlzJTI5LmF0dHIlMjglMjdpZCUyNyUyOSUzQiUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMGlmJTIwJTI4dHlwZW9mJTIwcm93X2lkJTIwJTIxJTNEJTNEJTIwJTI3dW5kZWZpbmVkJTI3JTI5JTIwJTdCJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwdmFsdWUlMjAlM0QlMjByb3dfaWQucmVwbGFjZSUyOCUyMmNvbnRhaW5lci1ndXN0YS1tZW51LWl0ZW0tJTIyJTJDJTIwJTIyJTIyJTI5JTNCJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTdEJTIwJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwdmFyJTIwbl9vZmYlMjAlM0QlMjAlMjQlMjglMjclMjNjb250YWluZXItZ3VzdGEtbWVudS1pdGVtLSUyNyUyMCUyQiUyMHZhbHVlJTI5Lm9mZnNldCUyOCUyOSUzQiUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMHZhciUyMG5fdG9wJTIwJTNEJTIwbl9vZmYudG9wJTIwLSUyMDIwMCUzQiUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMHZhciUyMG5fYm90dG9tJTIwJTNEJTIwJTI0JTI4JTI3JTIzY29udGFpbmVyLWd1c3RhLW1lbnUtaXRlbS0lMjclMjAlMkIlMjB2YWx1ZSUyOS5oZWlnaHQlMjglMjklMjAlMkIlMjBuX3RvcCUzQiUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMGlmJTI4JTI0JTI4d2luZG93JTI5LnNjcm9sbFRvcCUyOCUyOSUyMCUzRSUzRCUyMG5fdG9wJTIwJTI2JTI2JTIwJTI0JTI4d2luZG93JTI5LnNjcm9sbFRvcCUyOCUyOSUyMCUzQyUzRCUyMG5fYm90dG9tJTI5JTIwJTdCJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTI0JTI4JTIyLnB1cnBvc2UtbmF2aWdhdGlvbiUyMGxpJTIyJTI5LnJlbW92ZUNsYXNzJTI4JTIyY3VycmVudC1tZW51LWl0ZW0lMjIlMjklM0IlMEElMDklMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjQlMjglMjcuZ3VzdGEtbWVudS1pdGVtLSUyNyUyMCUyQiUyMHZhbHVlJTI5LmFkZENsYXNzJTI4JTIyY3VycmVudC1tZW51LWl0ZW0lMjIlMjklM0IlMEElMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlMjAlN0QlMjAlMEElMDklMjAlMjAlMjBkZWxldGUlMjBuX3RvcCUzQiUwQSUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMCUyMGRlbGV0ZSUyMG5fYm90dG9tJTNCJTBBJTA5JTdEJTI5JTNCJTBBJTIwJTIwJTdEJTI5JTNCJTIwJTIwJTBBJTdEJTI5JTNCJTBBJTNDJTJGc2NyaXB0JTNF[/vc_raw_js][/vc_column][/vc_row]